Donald Trump’s latest round of public comments about his health — delivered in an interview and amplified across social media — has revived a familiar debate in American politics: how much the public can reasonably infer about a president’s fitness from snippets, impressions and self-reported “tests,” and how much remains unknowable without transparent medical disclosure.

In the interview, Trump portrayed himself as eager to prove mental sharpness, telling the interviewer that he enjoys taking what he described as “cognitive” tests and that he has “aced” them multiple times. His remarks were quickly recirculated by partisan outlets and creators, some of whom framed the exchange as reassurance, while others treated it as evidence of decline.

Trump also discussed continuing to take aspirin despite saying doctors had recommended changes to his regimen, casting the decision as a matter of personal preference and routine. Medical specialists who have weighed in publicly in recent months have generally warned that daily aspirin use — particularly in older adults without a clear secondary-prevention indication — carries bleeding risks that can outweigh benefits, and that dosing should be individualized under clinical guidance.

The cognitive-testing boast, meanwhile, has drawn scrutiny because presidents have historically disclosed widely varying levels of medical detail, and because “acing” a brief screening tool does not, by itself, settle questions about impairment. One commonly discussed screening instrument, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), is designed to flag potential cognitive issues and is not a standalone diagnostic for dementia. Clinicians typically caution that performance can be influenced by factors like education, anxiety, fatigue and testing familiarity — and that a meaningful evaluation depends on longitudinal observation, clinical context and, when warranted, more comprehensive neuropsychological assessment.

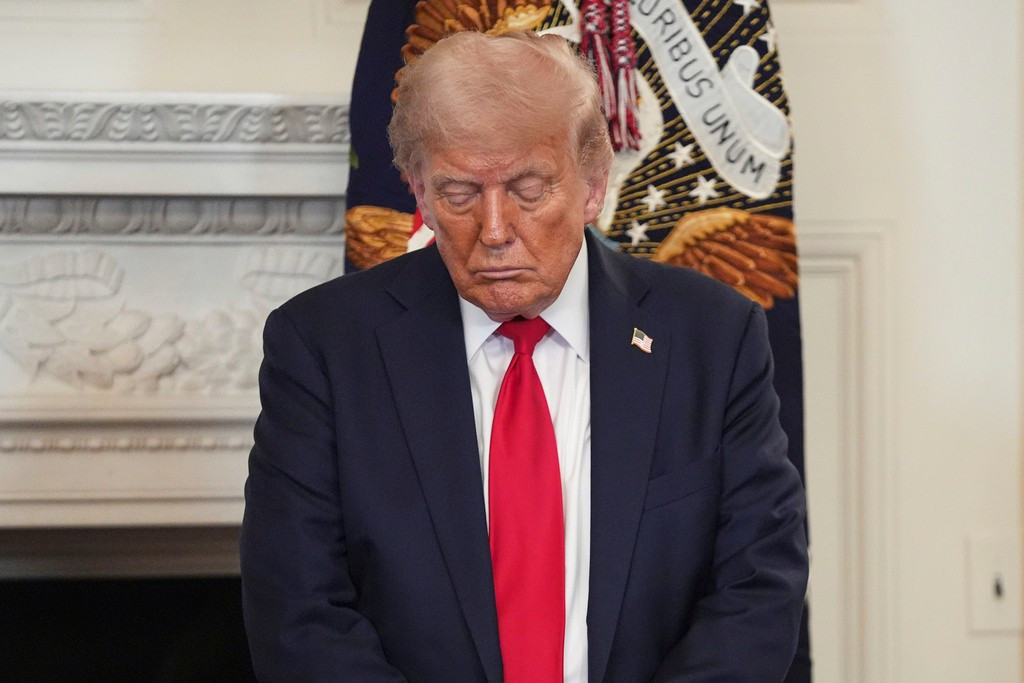

The renewed attention comes amid a broader media cycle that has increasingly treated Trump’s physical presentation — bruising, gait, verbal wandering, and unusually combative exchanges — as political material. A recent Reuters report, citing physician commentary, noted concerns raised by some doctors about visible bruising and Trump’s reported aspirin use, while also underscoring the limits of assessing any individual without access to medical records. Other coverage, including reporting tied to accounts of Trump’s routines and medical choices, has similarly fueled speculation but stopped short of clinical conclusions.

That gap — between public performance and private medical facts — is where the most heated interpretations flourish. In the hours after the interview circulated, social platforms filled with split-screen clips and stitched montages: Trump’s own claim that he would “know” if age ever impaired him set against moments where critics argued he appeared distracted or irritable. Some supporters framed the same moments as evidence of toughness and stamina under pressure.

The White House has repeatedly insisted the president is fit for duty and has pointed to physician letters and routine physicals, but has not offered the kind of detailed, standardized cognitive documentation that would likely quiet speculation. That choice reflects a longstanding tension: presidents have powerful incentives to project vitality, while voters and lawmakers have legitimate interests in basic transparency about a leader’s capacity to execute the office.

Health experts say the more responsible public conversation is often the least satisfying to partisan audiences: it is possible for a public figure to exhibit off-the-cuff verbal oddities, mood volatility or meandering speech without meeting criteria for a specific neurodegenerative diagnosis; and it is also possible for early impairment to be subtle enough that casual observers miss it. The most reliable signal, clinicians emphasize, is change over time measured in structured ways — not viral clips.

In practice, structured ways are precisely what the public rarely sees. Short cognitive screens can be useful, but they are not “IQ tests,” and they can be gamed through repetition. The MoCA itself is explicitly a screening tool; a strong score may be reassuring, but it is not definitive, and a weak score is typically a reason to evaluate further rather than a diagnosis on its own.

The political consequences of this ambiguity are already visible. Opponents argue that the country cannot afford guesswork about a president’s medical status, especially amid crises that demand sustained attention and careful judgment. Allies counter that critics are weaponizing age and that Trump’s willingness to discuss testing at all distinguishes him from predecessors. The result is a familiar American stalemate: one side demanding more disclosure, the other side insisting the existing disclosure is enough — and everyone else left to interpret fragments.

For now, what is “known” publicly is narrower than the commentary suggests. Trump says he has taken and passed cognitive screens. He has also said he continues aspirin use in a way that has prompted public medical caution in press reports. Beyond that, the strongest claims circulating online — including armchair diagnoses and sweeping conclusions based on tone, facial expression, or isolated verbal slips — remain exactly that: speculation.

And yet the episode underscores a deeper reality of modern politics: in the absence of fuller disclosure, the public will continue to treat performance as proxy, and proxy as proof. In a media environment optimized for fragments, health — like everything else — becomes content.