When Allies Turn Away: Canada, Europe, and the End of America’s Central Role

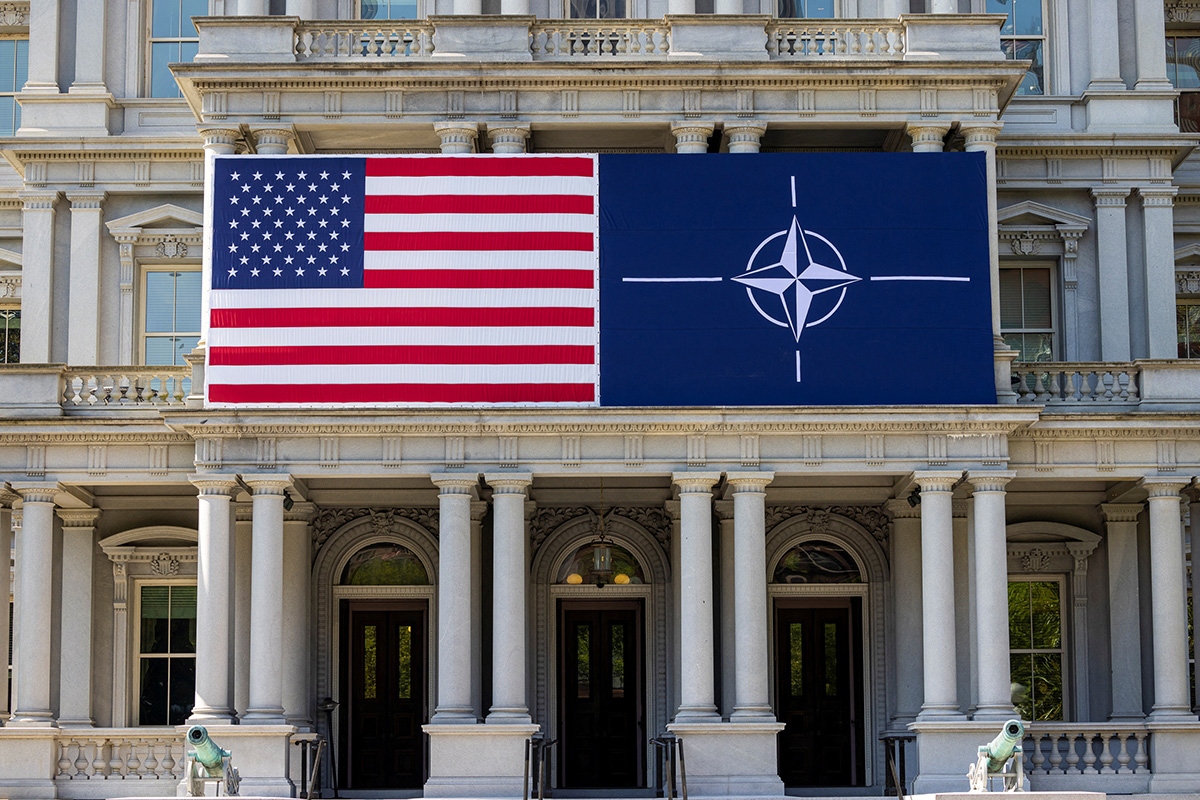

For more than eight decades, the Western security order rested on an assumption so deeply ingrained it rarely needed to be stated: the United States was indispensable. Washington led NATO, anchored defense supply chains, shaped the rules of international engagement, and—most importantly—was trusted by its allies. That assumption is now collapsing.

On January 8, 2026, French President Emmanuel Macron spoke with striking bluntness before France’s ambassadors at the Élysée Palace. The United States, he said, was turning away from its allies and breaking free from the very international rules it had once promoted and enforced. A day earlier, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier issued an equally stark warning, cautioning that the world was becoming a “den of thieves,” where the most unscrupulous actors seize whatever they want and entire regions are treated as the property of a few major powers.

These were not emotional outbursts or offhand remarks. They were carefully prepared speeches, delivered to diplomatic corps, broadcast internationally, and timed to send a clear signal: Europe no longer considers the United States a reliable guardian of the rules-based international order.

They also marked a turning point in a deeper structural shift already underway. Canada and Europe are now building a formal security architecture that deliberately functions without American coordination.

Canada Chooses a Different Path

When Mark Carney was sworn in as Canada’s prime minister in March 2025, diplomatic tradition dictated that his first foreign trip would be to Washington. Canadian leaders, regardless of party, have historically used that first visit to reaffirm the “special relationship” with the United States.

Carney broke that tradition. His first trips were to Paris and London.

In Paris, he met President Macron and declared that Canada was “the most European of non-European countries,” promising to be a reliable and trustworthy partner. Switching between French and English, Carney emphasized shared values, institutional stability, and respect for international law. In London, he met Prime Minister Keir Starmer and held a private audience with King Charles III—a symbolic homecoming for a man who had served as governor of the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020, the first non-Briton to do so in the institution’s 300-year history.

The symbolism was unmistakable. Canada was signaling where it believed its future lay.

This pivot came as President Donald Trump publicly threatened to annex Canada as the “51st state,” imposed sweeping tariffs on Canadian goods, and mocked Ottawa’s leadership. From London, Carney responded bluntly, calling the annexation rhetoric “unthinkable” and “disrespectful,” and stating that such comments would need to stop before any serious conversation about bilateral partnership could resume.

He also disclosed that Canada was reconsidering its planned purchases of American-made F-35 fighter jets and was instead discussing deeper military and security cooperation with European partners.

From Symbolism to Structure

The shift became institutional on June 23, 2025, when Canada and the European Union signed a Security and Defence Partnership. The agreement created a formal framework for coordination on defense procurement, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence governance, and military capability development.

At its core was a strategic objective: reducing Canada’s dependence on American defense suppliers.

For decades, Canada’s military procurement had been deeply embedded in U.S. supply chains and strategic planning. Under the new partnership, Canada began negotiations to participate in SAFE, the European Union’s €150 billion joint defense procurement loan facility, part of a broader €800 billion European rearmament initiative. SAFE allows participating countries to pool purchasing power, standardize equipment, and negotiate collectively with defense manufacturers.

By joining SAFE, Canada would increasingly procure military equipment through European supply chains and adopt European standards, aligning its defense planning with Europe rather than Washington.

What was most notable about these announcements was what they omitted. There was no mention of U.S. coordination. No reference to American approval. No suggestion that Washington remained the indispensable intermediary.

Canada was not opposing the United States. It was simply building a system that no longer depended on it.

Greenland and the Breaking Point

If one issue crystallized European and Canadian alarm, it was Greenland.

President Trump’s repeated refusal to rule out the use of military force to seize Greenland—a self-governing territory of Denmark—crossed a threshold few allies believed an American president would ever approach. Greenland’s strategic location and rare earth resources made it geopolitically valuable, but the rhetoric surrounding its potential annexation alarmed governments across Europe.

On January 7, 2026, seven NATO countries—France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Canada—issued a joint statement affirming Greenland’s sovereignty and Denmark’s territorial integrity. This was unprecedented: NATO allies publicly coordinating against an American territorial claim.

Canada went further. Prime Minister Carney met Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen in Paris and announced that Canada would open a new consulate in Greenland. He also confirmed that Canada’s governor general and foreign minister would visit the territory, a highly symbolic act intended to demonstrate solidarity with Denmark and support for Greenland’s right to determine its own future.

The implication was unmistakable. Where Canada and Europe pledged adherence to international law, they no longer assumed the United States would do the same.

Trust, Once Lost, Does Not Return Easily

Public opinion has shifted alongside policy. A January 2026 poll by Germany’s ARD broadcaster found that 76 percent of Germans no longer viewed the United States as a reliable partner. Nearly the same number doubted that NATO could depend on American protection. In Canada, polling showed overwhelming opposition to any form of political integration with the United States.

These numbers matter because they reflect a deeper conclusion reached by governments: strategic trust has been broken.

And trust, once lost, is not restored by a single election or a change in tone from the White House.

The infrastructure now being built—European-Canadian defense supply chains, standardized procurement systems, long-term contracts, shared intelligence frameworks—creates path dependency. Once these systems are operational, reversing them becomes economically and strategically irrational.

American companies will not be banned from European or Canadian markets. But their role will change. They will participate as contractors, not as pillars of an American-led system.

The Cost of Coercion

The Trump administration assumed that American power was sufficient to compel allied compliance. It assumed threats would produce obedience and that allies lacked viable alternatives. Those assumptions proved wrong.

When allies conclude they are being coerced rather than protected, they do not become more compliant. They seek independence.

What is emerging between Canada and Europe is not an anti-American alliance but an adaptation to a world in which U.S. leadership can no longer be taken for granted. It marks the end of automatic American centrality in Western security, the end of deference to Washington as the default coordinator of allied strategy.

For 80 years, U.S. leadership was assumed. That era has now ended—not through formal rupture, but through institutional replacement.

And once those institutions exist, military power alone cannot undo them.