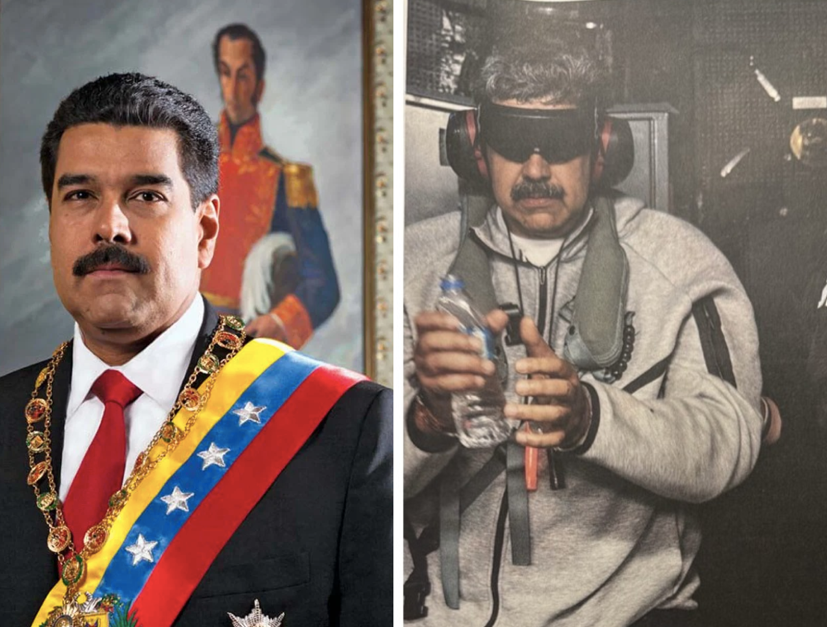

China on Sunday sharply criticized the United States after American forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, framing the operation as a violation of international law and a destabilizing escalation in Latin America. But behind Beijing’s diplomatic language lies a more concrete concern: the future of China’s deep economic and strategic stake in Venezuela, built over two decades through loans, oil-for-debt agreements, and major infrastructure projects.

In a statement unusually direct by the standards of Chinese diplomacy, the Chinese Foreign Ministry demanded that Washington guarantee the personal safety of Mr. Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores; release them immediately; halt efforts to overthrow Venezuela’s government; and resolve disputes through “dialogue and negotiation.” The ministry condemned the operation as a breach of “international law and the basic norms of international relations,” and warned that it threatened regional peace and security.

Those demands amount to a public rebuke of Washington’s actions — and a signal that Beijing sees the United States not merely as confronting a single government, but as rewriting the terms of power in a region where China has invested heavily and expanded its influence.

A high-stakes investment

Venezuela has been one of China’s most significant bets in the developing world and one of its largest commitments in Latin America. Over roughly two decades, Chinese state banks and companies have extended tens of billions of dollars in financing, much of it structured around oil shipments, while Chinese firms have embedded themselves in Venezuela’s energy sector and broader economy.

The precise totals vary by accounting method and time period, but the broad scale is undisputed: China’s exposure is measured in the tens of billions of dollars, with far larger sums associated with long-term projects, joint ventures, and commercial arrangements. The capture of Mr. Maduro raises immediate questions about whether those commitments will be protected if Venezuela’s political order shifts — and, crucially for Beijing, who will control Venezuela’s oil flows and contracts going forward.

The concern is not theoretical. When governments change, successor administrations sometimes challenge the legitimacy of contracts and debts incurred under previous leaders, especially when those agreements are tied to political alliances. China has faced such risks elsewhere, and analysts have long noted that Venezuela — heavily indebted, economically fragile, and politically volatile — presents an unusually complex case.

Beijing’s outrage — and its limits

Chinese official statements combined legal language with political accusation. The Foreign Ministry described the American operation as “hegemonic behavior” and said it “firmly opposes the use of force against a sovereign state.” Chinese state media struck an even harder tone. An editorial published by Xinhua, the state-run news agency, argued that the operation reflected Washington’s reliance on unilateral force and undercut decades of American rhetoric about defending a rules-based international order.

The Global Times, a nationalist tabloid often used to amplify more combative arguments, emphasized the shock of a head of state being seized and referenced the military sophistication of the operation, citing analysts who described U.S. electronic warfare capabilities and special operations effectiveness.

Yet Beijing’s response also reflects an uncomfortable reality: China has extensive interests in Venezuela, but limited tools to protect them directly. It can marshal diplomatic pressure, build coalitions at the United Nations, and impose selective economic costs. But China does not have the military footprint in the hemisphere to reverse events on the ground.

That imbalance is part of the story. As one analyst put it in a widely cited comparison in recent years, the United States maintains a global network of military facilities, while China’s overseas basing footprint is far smaller. Venezuela is geographically distant from China’s core theaters of influence and close to America’s.

Trump’s message: oil will flow — but on U.S. terms

Complicating Beijing’s reaction were remarks from President Trump, who suggested publicly that Chinese access to oil might not be cut off. In comments attributed to him in U.S. television interviews, Mr. Trump indicated that “they’re going to get oil,” while also suggesting that Washington would oversee Venezuelan production and exports and that U.S. companies would play a central role in repairing and operating the country’s damaged oil infrastructure.

For China, the implication is not simply about supply. It is about leverage. If the United States becomes the gatekeeper of Venezuelan crude — deciding who receives it, under what contracts, and on what terms — Beijing’s position shifts from partner to dependent customer. That would represent a fundamental change in the balance of influence in one of China’s signature relationships in Latin America.

The oil dimension is central because Venezuela’s reserves are vast by global standards, and its exports have long been intertwined with debt repayment. Under various arrangements, Venezuelan shipments have been routed to Chinese buyers, and Chinese state oil companies have participated in upstream projects and joint ventures. If those contracts are revised under a government aligned with Washington, China could find itself competing against returning Western firms under less favorable conditions.

A diplomatic collision course at the United Nations

China’s condemnation came as Venezuela and Colombia sought an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council, backed by Russia and China. Venezuela’s ambassador has framed the episode as foreign aggression aimed at dismantling the country’s political system, while China’s UN envoy has repeatedly warned against what Beijing describes as unilateralism and coercion.

The United States, as a permanent member of the Council, holds veto power, making any binding resolution unlikely. Still, the meeting carries symbolic weight: it provides a platform for Beijing and Moscow to isolate Washington diplomatically, reinforce arguments about sovereignty, and frame the episode as part of a broader struggle over international order.

Russia’s reaction was swift and emphatic, casting the operation as “armed aggression” and rejecting U.S. legal justification. Iran and North Korea issued condemnations as well, each warning that the precedent undermines sovereignty and global stability. In North Korea, state media described the event as proof of American “rogue” behavior, and analysts noted that subsequent missile launches — the first of the year — could be read as a signal of deterrence and resolve.

The alignment is notable because these governments do not always coordinate closely. But the shared message on Venezuela — that Washington has crossed a line — reflects a wider anxiety among authoritarian and adversarial states: if a head of state can be seized and transported to face foreign legal proceedings, then formal norms may offer little protection against power.

Latin America divided

Regional reactions, as described by multiple accounts, were mixed. Leaders on the left, including Brazil’s president, condemned the operation as an unacceptable escalation and invoked a history of foreign interference in the hemisphere. Colombia’s government raised concerns about refugee flows and instability. Mexico urged restraint and emphasized nonintervention.

Other governments, particularly those more hostile to Mr. Maduro, welcomed his removal or treated it as an opportunity for political transition. The split reflects long-standing divisions in Latin America over Venezuela itself: for some, Mr. Maduro represents repression and economic collapse; for others, he symbolizes resistance to U.S. pressure and intervention.

That divide may shape what comes next. Even if Beijing mobilizes diplomatic opposition, Washington’s ability to build a regional coalition — or to prevent one from forming against it — could determine whether this crisis becomes a sustained international confrontation or a rapid consolidation of a new Venezuelan order.

A public echo inside China

The episode also reverberated within China. Discussion surged on Chinese social media platforms, where users reportedly drew comparisons between Venezuela and other contested geopolitical situations, including Taiwan. Some commentators interpreted the operation as evidence of American willingness to use force to achieve political outcomes; others debated whether it offered lessons — positive or negative — for China’s own strategic planning.

For Beijing, that domestic reaction is a double-edged sword. Public scrutiny raises pressure for a strong response, but a dramatic escalation could carry real economic and diplomatic costs, especially at a time when U.S.-China relations remain tense and global markets remain sensitive to geopolitical shocks.

The question Beijing cannot avoid

The immediate crisis centers on Mr. Maduro’s fate and Venezuela’s political future. But for China, the larger question is what happens to the architecture of influence it has built in Latin America — and whether the United States is prepared to challenge it directly in the region, not only through diplomacy, but through force and control of critical resources.

Beijing can condemn the operation, press for a Security Council debate, and warn of consequences. What it cannot do is undo the capture or guarantee that a new Venezuelan government, shaped under American pressure, will honor China’s financial and energy arrangements.

In that sense, the confrontation is less about a single event than about a shifting global order. Venezuela, once viewed primarily as a regional crisis, has become a stage for great-power competition — where sovereignty, oil, and influence are inseparable, and where the rules appear increasingly contingent on power.