Epstein Files Reignite Trauma for Survivors, Raising Questions About Accountability and Disclosure

NEW YORK — For survivors of sexual abuse linked to Jeffrey Epstein, the recent release of millions of government documents was expected to offer transparency and accountability. Instead, several survivors say it has reopened wounds, exposed private information, and raised new concerns about how institutions charged with protecting victims are handling one of the most consequential abuse scandals in modern history.

Among those speaking publicly is Anushka de Georgia, who has described the document release as deeply retraumatizing. In interviews and public statements, she and other survivors say identifying details — including addresses, signatures, and personal records — appeared in the released materials despite long-standing assurances that such information would be carefully redacted.

“You can’t put that back,” Ms. de Georgia said, describing the moment she learned that sensitive personal data tied to her testimony had become publicly accessible. Like many survivors, she said she had cooperated with investigators and courts under the expectation that her privacy would be protected.

The Department of Justice has acknowledged that errors occurred during the document release and has since removed and revised thousands of pages. Officials said the process involved an extraordinary volume of records and that corrections were underway. Survivor advocates, however, argue that the mistakes reflect systemic failures rather than isolated oversights.

Legal experts note that protecting victim identities is a foundational obligation in cases involving sexual exploitation, particularly when survivors were minors at the time of abuse. “This is not a novel challenge for prosecutors,” said one former federal official familiar with such cases. “Redaction is basic, but the consequences of getting it wrong are severe.”

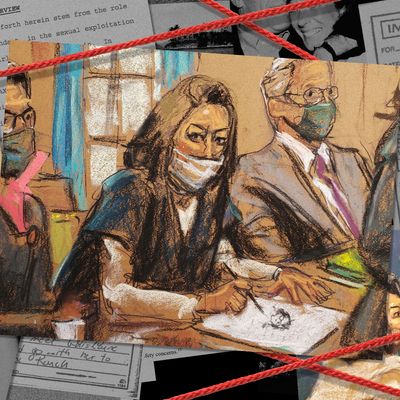

The renewed scrutiny comes years after Epstein’s death in federal custody in 2019 and the subsequent prosecution of Ghislaine Maxwell, who was convicted in 2021 of child sex trafficking-related offenses and sentenced to federal prison. While Ms. Maxwell’s conviction was seen by many survivors as a measure of accountability, it did not end the legal or emotional toll.

Ms. de Georgia testified during the Maxwell proceedings, recounting experiences that began when she was a teenager and describing a pattern of grooming, coercion, and abuse. She has emphasized that her decision to speak publicly was not made lightly and followed years of anonymity, therapy, and recovery.

Survivors and their advocates say the latest developments underscore a persistent imbalance: victims are repeatedly asked to relive trauma in service of justice, while institutions struggle to meet their most basic responsibilities.

The release of the Epstein-related files has also reignited debate over how much information remains undisclosed. Lawmakers and transparency advocates have noted that the recent disclosure represents only a portion of the total records compiled across years of investigations and litigation. The Justice Department has said it does not plan additional large-scale releases, a position that has frustrated survivors seeking fuller accounting.

Some survivors fear that the fragmented release of documents — mixing verified records with uncontextualized material — risks fueling misinformation that can be weaponized against those who come forward. “When inaccurate narratives circulate, they don’t just confuse the public,” Ms. de Georgia said. “They actively undermine survivors’ credibility.”

Beyond the legal questions, survivors describe ongoing personal consequences: harassment, threats, and disruptions to family and professional life. Several have said that public exposure has forced relocations, heightened security concerns, and renewed struggles with post-traumatic stress.

Mental health specialists note that such outcomes are common when survivors are thrust back into public view without adequate safeguards. “Trauma doesn’t exist in the past tense,” said a clinician who works with abuse survivors. “Institutional actions in the present can either support healing or compound harm.”

Despite these challenges, survivors like Ms. de Georgia say they remain committed to speaking out. They point to those who are no longer alive to tell their stories and describe their advocacy as a form of responsibility as much as resistance.

The broader implications extend beyond a single case. The Epstein scandal has become a measure of how the justice system handles powerful offenders, complex networks, and vulnerable victims. Each misstep, survivors argue, risks reinforcing the very dynamics that allowed abuse to persist for years.

For now, the focus among survivors is not on political outcomes or public spectacle, but on accountability and reform: stronger protections for victim data, clearer standards for document releases, and meaningful inclusion of survivor voices in decisions that affect them.

“This is not about headlines,” Ms. de Georgia said. “It’s about whether the people who were harmed are finally treated as human beings — not collateral damage.”

As investigations fade from the front pages and legal proceedings conclude, survivors say their lives do not return to normal. For them, the question remains whether the institutions that failed them once are willing — or able — to do better now.