By XAMXAM

In the days leading up to Super Bowl LX in Santa Clara, when attention is typically fixed on matchups, commercials, and halftime speculation, Donald Trump found himself confronted with an altogether different kind of pregame spectacle. It did not come from a debate stage, a courtroom, or a campaign rally. Instead, it arrived through protest art, resurfaced cultural artifacts, and a growing unease around the political symbolism now orbiting America’s most watched sporting event.

The trigger was not a single incident but a convergence. Conservative groups announced plans for an alternative halftime-style protest featuring Kid Rock, a longtime Trump ally. Almost simultaneously, a 2001 Kid Rock song resurfaced online, drawing scrutiny for lyrics referencing underage girls. The timing proved unforgiving. What was intended as a countercultural show of loyalty quickly became another reminder of how culture-war gestures can rebound in unexpected ways.

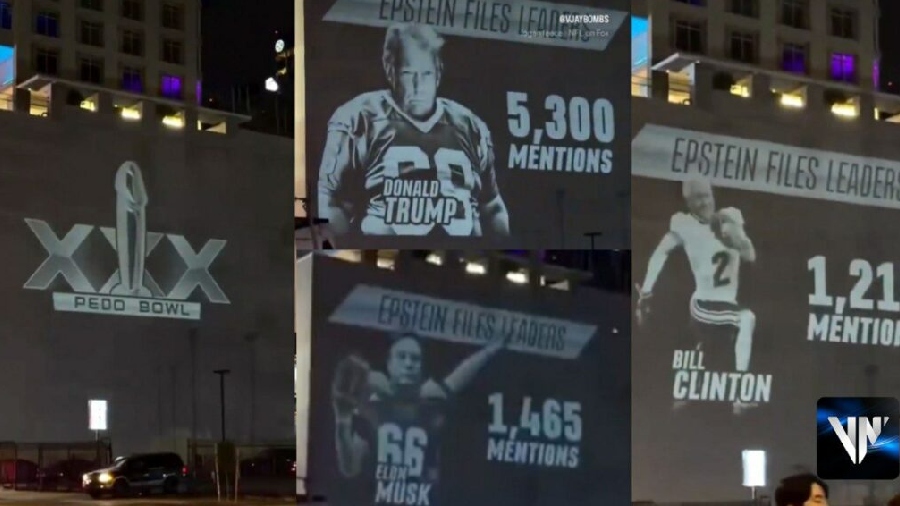

Yet the sharper blow came not from music, but from images projected onto buildings across Los Angeles in the nights leading up to the game. The projections, created by the street artist known as VJ Bombs, reimagined Super Bowl iconography through the lens of the long-running Jeffrey Epstein scandal. Logos were altered. Scoreboards became tallies of names. Familiar pageantry was replaced with unsettling associations.

One widely shared projection depicted a mock “scoreboard” listing figures allegedly mentioned in Epstein-related files. Trump’s name appeared most prominently, a visual choice that echoed years of speculation, denial, and deflection surrounding his past social proximity to Epstein. Other powerful figures—business leaders, political operatives, and media personalities—were included as well, reinforcing the artist’s stated message that the scandal transcends partisan boundaries.

The images spread rapidly online, accumulating millions of views within hours. Their power lay less in explicit accusation than in implication. They did not argue a case; they juxtaposed symbols Americans know intimately with names many would rather keep abstract. In doing so, they disrupted the carefully managed narratives that often surround both Trump and the Super Bowl itself.

For Trump, the moment was especially awkward. He has long treated the Super Bowl as a cultural proving ground, a stage where national identity, masculinity, and spectacle converge. Past appearances and comments have framed the event as a validation of a certain version of America—one aligned with dominance, celebrity, and unapologetic confidence. The protest art inverted that framing, turning the event into a mirror reflecting reputational vulnerability instead.

The backlash was immediate in conservative media circles, where commentators dismissed the projections as tasteless, unfair, or desperate. Supporters accused artists and activists of politicizing sports, even as many of the same voices defended overtly political gestures when they aligned with Trump’s message. The familiar argument—sports should be neutral—surfaced again, revealing its selective application.

What distinguished this episode from earlier controversies was its asymmetry. There was no clear opponent for Trump to attack, no single organizer to ridicule, no debate format to dominate. The projections appeared, circulated, and lingered without inviting direct confrontation. They functioned more like ambient pressure than a frontal assault.

Adding to the discomfort was the broader context of the Epstein files themselves. While no new definitive legal findings were announced in the days before the game, renewed discussion of document releases and redactions kept the issue alive in public consciousness. For Trump, who has alternated between dismissing the scandal and calling for selective transparency, the timing was unhelpful. The Super Bowl spotlight amplified everything around it, including unresolved questions.

Political analysts noted that the episode underscored a recurring challenge for Trump: his reliance on spectacle leaves him vulnerable to counter-spectacle. When politics is framed as entertainment, critics need only disrupt the show to shift the narrative. In this case, the disruption did not come from journalists or opponents, but from artists repurposing the language of mass entertainment itself.

There is also a generational element at play. Younger audiences, less tethered to traditional broadcast media, encountered the protest images first through social platforms rather than television. For them, the Super Bowl is as much a digital event as a televised one, and meaning is shaped by memes, clips, and overlays as much as by the game on the field. In that ecosystem, symbolic interventions can travel faster than official responses.

By Sunday evening, as kickoff approached, the projections had disappeared from building facades, but not from feeds. Trump did not directly address them. He did not need to. Their impact lay in forcing an association rather than provoking a rebuttal. They ensured that, amid the commercials and choreography, another storyline hovered just out of frame.

The Super Bowl has always been more than a game. It is a ritual of American self-presentation, an annual exercise in deciding what deserves celebration. This year, on the eve of Super Bowl LX, that ritual included an uncomfortable reminder: in a culture saturated with images, control over the spectacle is never guaranteed.