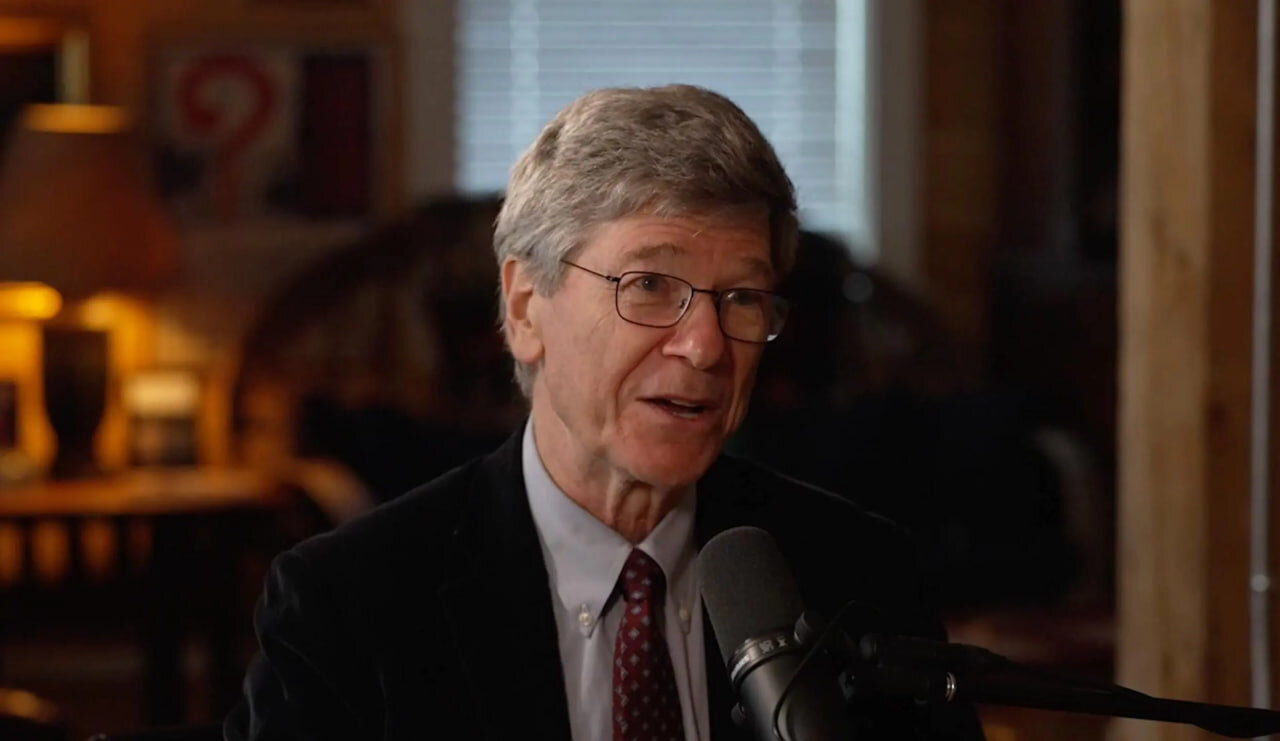

UNITED NATIONS — In an emergency session convened after the United States carried out a military operation in Venezuela and captured President Nicolás Maduro, Jeffrey D. Sachs, the economist and Columbia University professor, delivered a sweeping critique of American foreign policy and a pointed warning about what he called a growing collapse of the rules meant to restrain great powers.

Mr. Sachs, invited to brief the Security Council, argued that the central question before the body was not the nature of Venezuela’s government or the character of its leader. Instead, he said, the issue was whether any member state has the right “by force, coercion, or economic strangulation” to determine another country’s political future or control its affairs.

That question, he told the Council, goes directly to Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, which prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. The Council, he said, faces a stark choice: uphold that prohibition or allow it to erode. The consequences of abandoning it, he warned, would be “of the gravest kind,” especially in what he called the nuclear age.

Mr. Sachs’s remarks, while grounded in familiar debates over sovereignty and intervention, were unusually direct for the forum. He framed the Venezuela episode as the latest chapter in a long pattern of American “regime change” policies that, in his view, have repeatedly violated international law and produced lasting instability.

A broader indictment of U.S. policy

Mr. Sachs traced the argument back to the early Cold War, contending that since 1947 the United States has “repeatedly employed force, covert action, and political manipulation” to bring about political change abroad. He cited a scholarly book — “Covert Regime Change,” by the political scientist Lindsey O’Rourke — which he said documented 70 attempted American regime-change operations between 1947 and 1989.

He emphasized that, in his telling, such practices did not end after the Soviet Union’s collapse. Since 1989, he said, major U.S. operations undertaken without Security Council authorization have included Iraq in 2003, Libya in 2011, Syria beginning in 2011, Honduras in 2009, Ukraine in 2014, and Venezuela from 2002 onward.

He described what he called a recurring toolkit: open warfare, covert intelligence operations, support for armed groups, political destabilization, manipulation of media, bribery, targeted killings, “false flag operations,” and economic measures intended to weaken governments. These methods, he argued, are illegal under the U.N. Charter and tend to result in violence, prolonged conflict, and civilian suffering.

The goal of his historical overview was not merely to catalog interventions, but to argue that the Council’s credibility depends on whether it treats Article 2(4) as binding law rather than a principle applied selectively.

Venezuela as a case study

Turning to Venezuela specifically, Mr. Sachs argued that American efforts to influence the country’s political trajectory have spanned more than two decades.

He asserted that in April 2002 the United States knew of and approved an attempted coup against the Venezuelan government. He said that during the 2010s, the United States funded civil society groups engaged in anti-government protests and then responded to the government’s crackdown with sanctions.

Mr. Sachs cited a 2015 executive action in which President Barack Obama declared Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to U.S. national security — a phrase the Obama administration described as a legal formulation tied to sanctions authorities, but which critics have long used to argue that Washington exaggerated Caracas’s threat.

Under President Trump’s first term, Mr. Sachs said, the confrontation sharpened. He told the Council that Mr. Trump publicly discussed the possibility of invading Venezuela to overthrow the government during a 2017 dinner with Latin American leaders on the margins of the U.N. General Assembly.

He also pointed to the period from 2017 to 2020, when the United States imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA. Mr. Sachs cited steep declines in oil production and living standards during those years, presenting them as evidence that sanctions functioned as a form of economic warfare.

The U.N. General Assembly, he added, has repeatedly opposed unilateral coercive measures. Under the U.N. system, binding sanctions authority rests with the Security Council, not individual states — a point frequently emphasized by governments that oppose U.S. and European sanctions regimes.

Mr. Sachs also cited January 2019, when the United States recognized Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president, and later froze billions of dollars in Venezuelan assets held abroad. Those actions, he argued, were part of a continuing attempt to reshape Venezuela’s internal politics from outside.

Claims about U.S. strikes and threats

Mr. Sachs expanded the argument beyond Venezuela by asserting that in the past year the United States carried out bombing operations in several countries without Security Council authorization and not in lawful self-defense as defined under the Charter. He listed Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, and Venezuela as targets, describing the pattern as unlawful and destabilizing.

He further claimed that in the past month President Trump issued direct threats against a number of U.N. member states, including Colombia, Denmark, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, and Venezuela, and said such threats contributed to a climate of coercion incompatible with the Charter’s purposes.

The thrust of his argument was that the Council should not treat legality as secondary to political sympathy or moral judgment about Venezuela’s leadership. Even if some governments view Mr. Maduro as illegitimate or repressive, Mr. Sachs said, that does not confer legal authority on another state to decide Venezuela’s fate by force.

“Not called upon to judge Maduro”

At the core of Mr. Sachs’s briefing was a distinction he returned to repeatedly: Security Council members, he said, are not convened to adjudicate whether Nicolás Maduro is a good leader or whether American intervention will produce “freedom” or “subjugation.”

They are called upon, he insisted, to defend the U.N. Charter as the central restraint on power politics.

To make the point, he invoked the realist school of international relations — associated with thinkers like John J. Mearsheimer — which describes global politics as a competition for power in a system without a world government. Realism, Mr. Sachs argued, accurately describes anarchy but does not offer a pathway to peace; its own conclusion is tragedy.

He then appealed to the 20th century’s institutional response to that tragedy: first the League of Nations after World War I, and then the United Nations after World War II. The failure to uphold international law in the 1930s, he said, paved the way for catastrophe. In the nuclear era, he warned, a repeat failure could be existential.

A list of recommendations

Mr. Sachs concluded by urging the Council to affirm a set of concrete steps:

-

That the United States cease explicit and implicit threats or uses of force against Venezuela.

-

That it terminate any naval quarantine or coercive military measures undertaken without Council authorization.

-

That it withdraw military assets positioned “for coercive purposes” in or around Venezuela.

-

That Venezuela adhere to its own obligations under the Charter and to human rights standards reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

-

That the U.N. secretary-general appoint a special envoy to engage Venezuelan and international stakeholders and report back within 14 days.

-

That all member states refrain from unilateral coercion or armed action outside Security Council authority.

His closing message was a warning and an appeal: peace and even the “survival of humanity,” he said, depend on whether the Charter remains a living instrument or is allowed to “wither into irrelevance.”

What happens next

Whether the Security Council acts on such recommendations is uncertain, particularly given the realities of veto power. But Mr. Sachs’s remarks entered the official record at a moment of acute tension: a dispute over Venezuela that has become, for many governments, a proxy for a larger struggle over sovereignty, intervention, and the durability of international law.

In that sense, his briefing was less an attempt to litigate Venezuela’s internal politics than to insist that the Council’s legitimacy hinges on a simpler principle: that rules prohibiting force should not be optional, even — and perhaps especially — for the most powerful states.