In a congressional hearing that began with the trappings of routine oversight and ended in something closer to a civics lesson gone wrong, Representative Ted Lieu confronted the nation’s top law enforcement official with a deceptively simple demand: clarity. What he received instead—shrugs, deferrals, and professions of uncertainty—has since become a case study in how opacity at the highest levels of government can corrode public trust.

The subject was the long-shadowed investigation into Jeffrey Epstein, whose crimes and connections have continued to haunt American institutions years after his death. The witness was the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, appearing before the House Judiciary Committee to account for what the bureau knows—and what it has done—with the evidence seized during Epstein’s 2019 arrest.

Lieu’s questioning began with facts that are not meaningfully disputed. The FBI searched Epstein’s Manhattan residence. Investigators recovered a safe. Major news organizations, including the New York Times, reported at the time that the safe contained illicit photographs. The director did not deny these points. Instead, he retreated to a familiar bureaucratic refrain: he did not have the catalog of evidence in front of him.

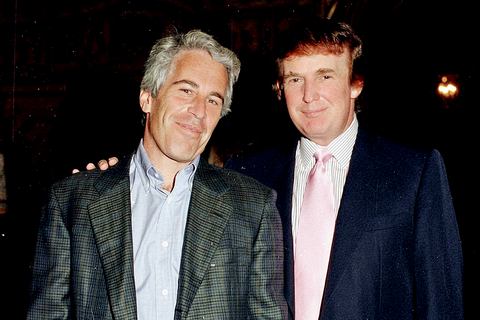

That posture, while common in Washington, proved insufficient. Lieu introduced public reporting by author Michael Wolff, who has stated that Epstein himself claimed the safe contained photographs involving Donald Trump and young women of uncertain age. Lieu did not ask the director to validate Wolff’s account on the spot. He asked something more basic and more damning: Had the FBI interviewed Wolff? Had it subpoenaed the tapes of Epstein’s recorded interviews? Had it exhaustively pursued the materials reportedly still held by the Epstein estate?

On each question, the answers amounted to some version of “I don’t know.”

The director attempted to reassure the committee by asserting that any damaging evidence involving Trump would have surfaced long ago, having been reviewed by multiple administrations and investigators over two decades. Lieu dismantled that assumption with a single counterexample: a previously undisclosed birthday message Trump wrote to Epstein, which emerged only years later through independent reporting, not proactive FBI disclosure. Confidence, Lieu suggested, is not evidence. Assumption is not investigation.

The exchange grew more unsettling whe n the discussion turned to subpoena power. The director suggested that the Epstein estate was under no obligation to comply with an FBI subpoena—a claim Lieu bluntly corrected. The bureau does, in fact, possess such authority. When the head of the FBI appears uncertain or evasive about the tools at his disposal, the concern shifts from capability to will.

The final questions should have been the easiest. Lieu asked whether specific high-profile individuals appeared on Epstein’s so-called client list. Not hypotheticals. Not accusations. Just yes or no. The director refused to answer, repeatedly deferring to previously released indexes and public materials. When asked directly whether Donald Trump appeared on that list, he did not say no.

That silence has echoed far beyond the hearing room.

This was not, as some would characterize it, a partisan ambush. It was an accountability test. Lieu did not allege guilt or demand conclusions. He asked whether the FBI has pursued every credible lead with equal vigor, regardless of whose name might be implicated. The director’s inability—or unwillingness—to provide clear answers under oath raises a troubling possibility: that the nation’s premier law enforcement agency is more comfortable managing perceptions than confronting uncomfortable facts.

The Epstein case has always been about more than one man’s crimes. It is about whether powerful institutions can investigate power itself without flinching. Transparency is not a courtesy in a democracy; it is a requirement. When law enforcement hedges instead of answers, the public is left to wonder who, exactly, the system is designed to protect.

Trust, once eroded, is difficult to restore. And in that hearing, the issue ceased to be Epstein. It became the credibility of the investigation—and the credibility of those entrusted to carry it out.