Trump’s Greenland Gambit Exposes Growing Strains on U.S. Alliances

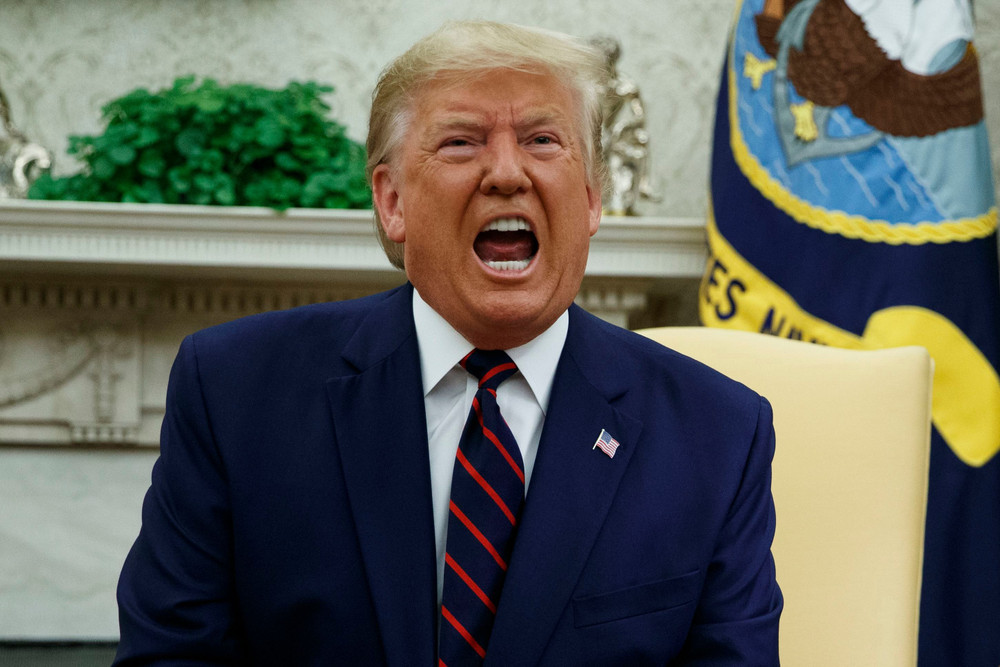

WASHINGTON — When Donald Trump revived the idea that the United States could acquire Greenland — by purchase or, as some administration officials openly acknowledged, by force — the reaction was swift and unusually severe. What once sounded like an offhand provocation has now evolved into a serious test of American credibility, alliance politics, and the limits of presidential power in foreign affairs.

According to reporting by The New York Times, Mr. Trump recently asked senior aides to provide updated options for bringing Greenland under U.S. control. While administration officials later stressed that diplomacy remained the preferred path, the White House conceded that military action was “always an option.” That admission alone alarmed lawmakers and allies, transforming what might have been dismissed as rhetoric into a genuine international concern.

An Ally, Not an Adversary

Greenland is a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, and both Denmark and the United States are founding members of NATO. Any military move against Greenland would therefore represent an unprecedented act: a NATO member using force against another NATO member’s territory.

European leaders responded quickly. In a joint statement, Denmark and several allied governments emphasized that “Greenland belongs to its people,” underscoring the principle of self-determination that has anchored postwar Western diplomacy. Privately, diplomats warned that even suggesting force against Greenland risked undermining the mutual trust on which NATO’s collective defense depends.

Security Claims and Disputed Facts

Mr. Trump has justified his interest in Greenland by invoking national security, arguing that Denmark is incapable of defending the island from Russian and Chinese encroachment in the Arctic. Yet U.S. and European officials say these claims exaggerate the threat.

The United States already maintains a strategic military presence on the island, including a long-standing air and space base, and cooperates closely with Denmark on Arctic defense. While Russia and China have increased activity in the region, analysts note that Greenland is not “surrounded” by hostile vessels, as Mr. Trump has claimed.

Even U.S. intelligence officials, speaking on background, have acknowledged that the president’s rhetoric overstates immediate dangers. “There is no sudden security vacuum in Greenland,” said one former defense official. “What exists is a long-term competition in the Arctic that is already being managed through alliances.”

Mixed Signals From Washington

Adding to the confusion has been the administration’s inconsistent messaging. Marco Rubio told lawmakers that the president preferred a negotiated purchase, echoing historical precedents like the Louisiana Purchase and the acquisition of Alaska. But comments from senior White House adviser Stephen Miller appeared to harden the tone, asserting that Greenland “should belong to the United States” and confirming that force had not been ruled out.

This pattern — escalating rhetoric followed by partial walk-backs — has become familiar to foreign governments. Diplomats say it complicates crisis management, as allies struggle to distinguish between negotiating tactics and genuine threats.

Republican Resistance Breaks the Pattern

Notably, opposition to the Greenland idea has not been confined to Democrats. Several prominent Republicans publicly rejected any suggestion of military action, warning that such a move would devastate America’s alliances and global standing.

The most consequential intervention came from Mike Pence, who served alongside Mr. Trump for four years. In a recent interview, Mr. Pence acknowledged that Greenland had been discussed during their administration but emphasized that those conversations focused exclusively on diplomacy and long-term cooperation.

“Denmark is a NATO ally,” Mr. Pence said, noting that any military assault on Greenland would force NATO members to choose between defending an ally or abandoning the alliance altogether. “Either way,” he added, “the alliance would be irreparably damaged.”

For many foreign policy experts, Mr. Pence’s comments stripped away what remained of the administration’s ambiguity. Coming from a former insider, they reinforced the view that the Greenland proposal — at least in its current form — represents a dangerous departure from established U.S. strategy.

A Familiar Political Pattern

Historians and political scientists see echoes of a broader pattern: leaders under domestic pressure turning outward to project strength. Mr. Trump has repeatedly warned Republicans that electoral losses could lead to investigations or impeachment, a message that has coincided with increasingly confrontational foreign policy rhetoric.

“External conflict has long been a tool for leaders facing internal challenges,” said a scholar of U.S. foreign policy. “The risk is that what begins as posturing can spiral into real-world consequences.”

In this case, those consequences would not be confined to a remote Arctic island. An American move against Greenland would challenge the foundational assumption that NATO members resolve disputes through diplomacy, not force.

Greenland as a Stress Test

Ultimately, the Greenland episode has become a stress test for the international order the United States helped build after World War II. That system depends less on raw power than on predictability, shared rules, and trust among allies.

Critics argue that treating territory and alliances as bargaining chips erodes those foundations. Supporters of the president counter that boldness is necessary in an era of great-power competition. But even some sympathetic voices question whether threatening an ally advances American interests.

As one former NATO ambassador put it, “Strength is not measured by how many allies you can intimidate, but by how many still choose to stand with you.”

An Unsettled Future

For now, Denmark has firmly rejected any notion of selling Greenland, and Greenland’s own leaders have reiterated that the island is not for sale. Congress has shown little appetite for endorsing drastic measures, and allied governments are watching closely for signs of de-escalation.

Whether the Greenland gambit fades or intensifies remains uncertain. What is clear is that it has already exposed the fragility of alliances in an age of political polarization and nationalist rhetoric. In doing so, it has raised a larger question for Washington and its partners: how much strain can the postwar alliance system endure before it begins to fracture?

In that sense, Greenland is less a prize than a warning — one that many in the United States and abroad hope will be heeded before rhetoric turns into irreversible action.